A True Prophecy from a Truly Eccentric Artist

My invitation came from H in a telegram, from Austria. Dressing for the United Nations that evening, I wore a black velvet shift with low back, black tights, black boots: my uniform for virtually all important events in the city’s winter months.

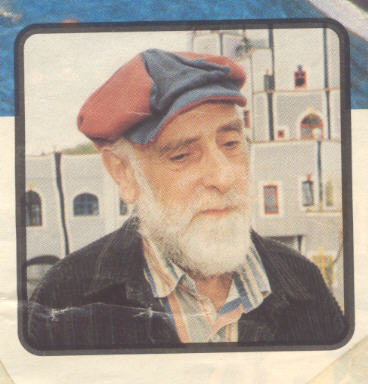

I was anxious to help my friend be acknowledged at such a noble institution as the UN. When I arrived, H greeted me in the main foyer with his customary almost-hug. I was delighted to see my mentor here in America, not his favorite place, he’d always told me. He asked me to stand by his side as he was touted, toasted, celebrated and chatted up by every ambassador from Albania to Zanzibar. Quietly, I fulfilled my role of escort for Hundertwasser, this now-deceased European master of unconvention, renowned for his naturalistic art and sensuous architecture—as well as his radical environmental activism.

Hundertwasser’s art

As one of the first to warn against the shameful industrialization of the West, people pressed to his side to praise his work, thanking Hundertwasser for his dedication to the world’s ecology problems. No one mentioned his Parisian and Berlin events back in the early sixties, those notorious happenings held by him—in the nude. In greeting the public about the world’s impending toxicity, H had always surrounded himself with a phalanx of stunningly naked young women to make sure his point got across about saving the Earth, when he gave those early press conferences designed to wake people up.

Now the time came for H to give his UN talk, when he’d explain the meaning of his commissioned stamps, those delightful abstract creations, enigmatic, embossed with real gold and silver. I remember as if it were last night. He approached the speaker’s podium in the informal hall where several hundred guests were gathered that evening in 1983, to celebrate the thirty-fifth anniversary of the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights, the historic event Hundertwasser’s colorful stamps commemorated. In sotto voce he read his speech as people strained to hear, even though H stood close to a microphone.

“I want to give homage,” he began, “to obscure freedoms people need to remember, besides the more obvious ones, such as liberating people from oppressive governments and ideologies, which others have chronicled ad infinitum.”

Everyone politely clapped.

“My designs honor each individual’s right to be what they want to become, to reach for the highest, and fulfill all our dreams. The first commemorates the right to honor the Earth and protect this garden planet we have come to forsake.” (exuberant applause) “The next stamp honors the right of each person to wear the clothes they want.”

At this everyone laughed. Per usual, H’s eccentric garb that evening was more costume than etiquette’s norm. A big soft hat set at a floppy angle. His buttoned jacket of deep indigo, too tightly fitting. His gaudy striped chartreuse pants, purposefully worn too short to expose mismatched crazy socks. H’s look more hippy bellbottom-vintage than the New Wave we were in, a time when people were just hearing about global warming and AIDS for the first time.

H cleared his throat. “However, the thing most dear to me and vital to civilization’s very survival, my next design celebrates the most basic of everyone’s life freedoms.”

H paused to look around at the expectant crowd. Uncontained murmurs erupted here and there from suave sophisticates. Everyone waited to see what could possibly be the most important, most basic of all human right—to this odd person, this world-class artist who’d publicly spoken of the devastating effects of pollution long before anyone, other than John Muir and Rachel Carson.

“That right,” H raised his voice, “is to be able to recycle one’s own waste by using humus toilets, thereby saving our dwindling water supplies from further contamination of human feces.”

The distinguished room broke into pandemonium! Disconcerted rumbles, shouts, and angry comments slapped the refined air.

I tried not to let my grin be too flagrant, but my face shone pridefully at my friend’s words. Courageously he was doing what I too, would do in the future: publicly express his need-to-be-heard opinions; using art as the message-medium, to help uplift humanity’s evolutionary course. And help balance the world’s increasing negativity with generating as much positivity as one can muster.

I beamed as my friend, one of the world’s most firmly committed eco-champions, stood before this top-of-the-cream audience that now rushed, en masse, for the exits—in shock, dismay, anger—beside themselves at being so “childishly treated by someone like him, not even a real artist,” I overheard a skeletal, mink-bedecked uptown matron say to her red-faced escort as they scurried past.

H shared all his views with me. “The more cultured people become, the more they’re removed from their basic animal natures,” he’d said. “My mission as artist is to bring to people’s attention how high they’ve put themselves up on the materialistic pedestal. Human society needs to be jolted from their self-delusion, be brought to their rightful place by owning their animal natures. And embrace all of Nature as part of themselves.

“Yes,” H said, “we are civilized, and yes, some of us are lucky to get educated. But we are still animals, even if very brainy types.”

Hundertwasser in front of a Hundert-haus