The Eyes of God, a True Story

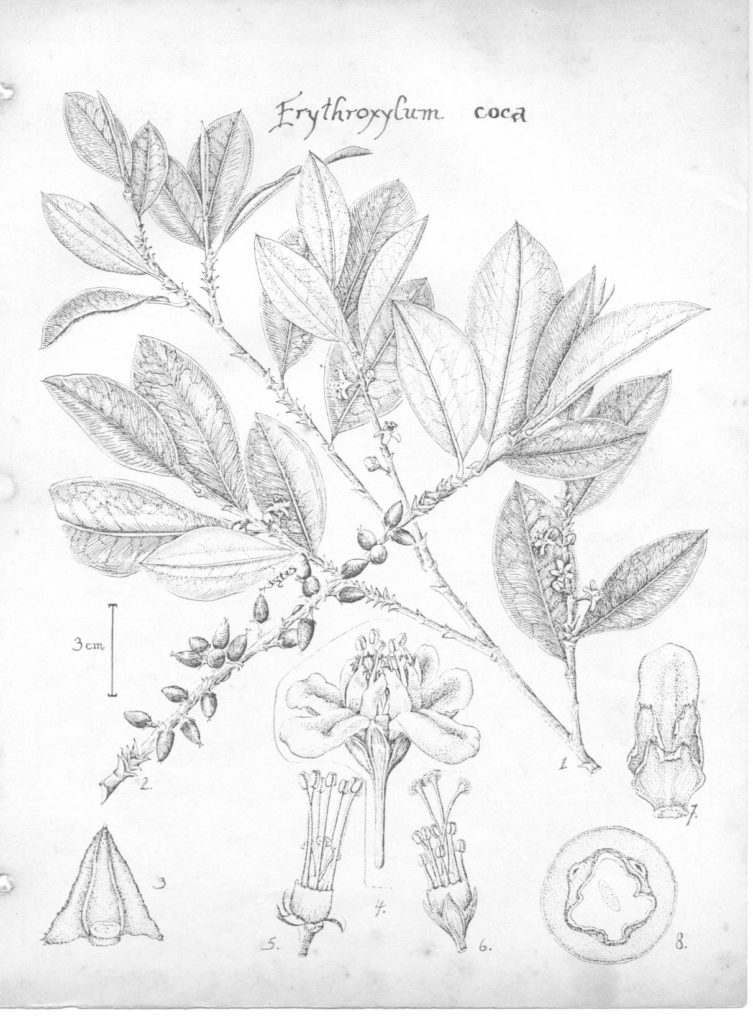

Erythroxylum coca, the bush cocaine comes from

I began my botanical career studying coca in South America.

When the Spanish first came and killed off nearly all the indigenous people, the remaining Incans knew their babies and their gold would all be taken from them. It was inevitable. So the people directly descended from the Ancient Ones met and made a pact with their Goddess, Mama Coca.

The Indians believed that their coca plants were the only power they had that could avenge the loss of life and the foreign, debasing culture the Europeans forced upon them. When the conquistadors took the coca leaves to use for themselves, the Indians smiled, because they knew one day these people would be weakened…and eventually be brought to ruin by Goddess Mama Coca’s all merciful goodness.

For eons the Indians had innocently chewed and brewed tea from the plant’s small roasted oval leaves. They were utterly repulsed, centuries later, when they learned of the white man’s desecrating the plant’s divinity by distilling a drug called cocaine from Her leaves, much less shoving it up their sorry, snotty noses. The Indians considered Mama Coca’s leaves as medicine, even as food, to be used sparingly for strength, valor, vigor and sustenance. Only with reverence did the Indians who revered the old ways, make use of the Goddess’ natural gifts that she lovingly bestowed upon Her children.

Carlos, el botanico y su perrito Pogo

Arrogant white men had taken the nutritious, mildly stimulating leaves back to Europe and made strong wines and elixirs from the leaves, then sold it as pep tonics and pick-me-up remedies, and eventually, intoxicating drinks, pills, and powders. During the slave era, government-run coca plantations sprung up in colonial West Indies to fuel the tropical lassitude of exhausted African slaves. They were given sweetened coca tea to drink in the heat of afternoon. Rum was doled out only at night, which the slaves naturally associated with relaxation, singing and partying with a rum-dumb glow after a long day under the sun, till they fell into a stupored sleep. Once the blacks of the Caribbean gained their freedom it was a no-brainer for them, en masse, to choose to become an alcohol-based culture instead of a coca-using one. The coca plantations the British and other West Indian colonial powers had cultivated for keeping the slaves at maximum output, quickly went to weed, choking out the coca bushes’ delicate root systems, and all that invigorating plant meant to the slaves as well.

###

Mama Coca, the spirit of the nutritious bush, never spoke to Her people. Her role to the Indians was to provide—literally everything—including their very lives. The Andes peoples’ ancient sun god, Wirak’ocha, like the sun god, Indri in India, and Ra in Egypt, among other deities that have communicated their messages through oracles, miracles, visions, or engraved tablets— transmitted universally similar messages to mankind:

Use your natural resources well, my children, for these are your wealth, your medicines, your food, your discoveries for betterment, and your earthly rewards. Everything you eat should be considered food of the gods. Everything you see here on this land is yours. Use it well, my children, for if you do it ill or cause it to disappear, it is your own lives that will sadly suffer. If you sin against nature, you sin against us, your protectors.

###

It was because of the unmerciful wrathfulness of cocaine’s highly addictive grip upon modern peoples of the world that I, Charles Bates, Carlos, to my friends—and now head botanist at the Field Museum—had been asked to study the growth patterns of the South American herbaceous drug plant, Erythroxylum coca. It was during these times of great unrest—political, social, and I daresay, my own—when I began my studies of coca. Its isolated drug form, cocaine, had already become the equivalent of a modern day plague, in the number of lives the drug and its Columbian cartel-cultivation had decimated, back in the States and abroad. Before things got even more out of hand than they were, the U.S. Government approached me about gathering coca data and assessing humanity’s love-hate affair with this plant.

While I struck out on my own, making innumerable field trips to gather coca specimens and data, back at our Chicago apartment awaited Zuma, my illustrator, lover, and secret sharer of my dreams. Together we studied plants that made powerful, inexorable impacts upon humanity’s search for life’s greater meaning.

###

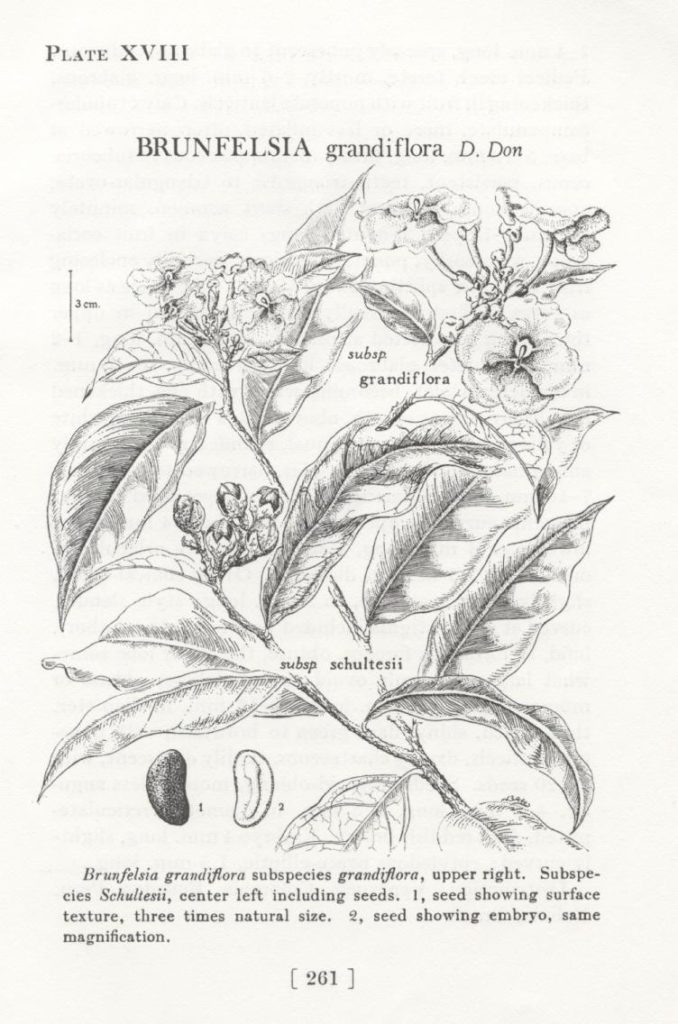

Over the years Zuma and I traveled to many locales in our attempts to learn all we could about the various plants we investigated. We were, I guess you could say, plant detectives. On this particular trip I want to tell you about, we’d flown to Jamaica, sponsored by a government grant. We were searching for a lost member of the Brunfelsia genus, a species called splendida. No specimens had been found of that particular species for many years. For all we botanists knew, it’d already been extinct at the time Zuma and I went looking for it. Back then, people were just waking up as to how quickly species of plants and animals were disappearing from the face of the earth. The two of us went looking, hoping against all odds, to find this missing link in our planet’s evolutionary story. Every plant, every animal, every organism has a unique page in the Earth’s story.

The only remaining specimens of splendida—a few pathetic twigs and brittle leaves glued onto yellowed, fragile sheets of mounting paper, and a jar containing some formaldehyde-preserved blossoms and seed pods—had been tested in a study at the Gray Herbarium, in Cambridge. Researchers had discovered splendida’s chemical compounds proved surprisingly more anti-carcinogenic than any other known species on earth.

Zuma and I agreed: we had to find it. With this plant back in our ecology, the future of humanity could perhaps forge a better route.

###

Making our way up the steep mountain road to the dusky oasis of refreshment, a typical West Indian shop, Zuma and I parked our rental car alongside the tall poinsettia bushes that bordered the dark little place. The hedge was in astoundingly full glory, its foliage a long line of screaming crimson capes, demarcating the shop’s entrance. Nowhere else had we ever seen these chest-high Christmas-blooming plants in such profusion as we did that day, in Jamaica. The shop was the only sign marking this place called Guavaberry, noted on the last collection of splendida’s old stained jar and fragile pressing found on a dusty shelf in the Gray Herbarium.

Zuma and I got out of our blue Fiat and walked into the crowded one-room establishment. People inside were talking, mostly ignoring the potpourri of essential native provisions: pails of pigs’ ears, lips and tails, all nicely sorted in their respective plastic buckets, along with bins of dried codfish for sale, over-perfumed pink soap, day-glo sodas, white bread and crackers, yellow store cheese, Red Stripe beer, Craven A and Three 5 cigarettes—and of course—the omnipresent white lightning rum.

It was noon. The cool, dark place was filled with the Jamaicans’ quiet chatter, as they relaxed from arduous work in their steep hillside gardens. The men held their shiny bladed machetes tightly clasped under strong, exultant arms; files used to sharpen them stuck out from back trouser pockets. Muscles bulged under loose cotton as a clean humus scent hung in the cool air alongside sour notes of yesterday’s rum being sweated out by these hardworking men and women. Everyone smiled broadly when Zuma and I walked in.

“Good morning,” the buoyant group offered us in friendly unison, a greeting spoken in all its many variations by these islanders, used to acknowledge any and all encounters with the lilting dignity of humble people.

I addressed the stout man behind the counter, explaining why we were there.

“Can you tell us if you’ve seen this plant?”

First I showed the shopkeeper, then everyone else a black and white drawing gleaned from the last known specimen, which had been collected right there in Guavaberry, back in the 1940s. What I showed these people was a densely foliated, small-leafed bush, its blossoms star shaped and profuse. To an untrained eye, it might appear to be a bush indiscernible from every other shrubby variety found in the tropics. Zuma’s rendition, however, was brilliant, like all her botanical illustrations. Someone had once said, “That Zuma—she draws like the wind.” And it was true. Because she’d drawn so many of splendida’s cousins—other members of the Brunfelsia clan—she could tap her intimate knowledge of that genus. Using only a few dried and pickled specimens, the only material available, Zuma used her imagination to create a reasonable drawing of this presumed-extinct plant. With scant, broken leaves, and glued-on, withered remains of what once had been splendida’s viable parts, wistfully found at the Gray, along with a jar filled with hundred-year-old pickled flowers and one mostly destroyed, already once-dissected fruit, whose seeds had been, for generations, worthless—from only that—Zuma had made her remarkably lifelike study of splendida.

“The common horticultural name for Brunfelsia is Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow,” Zuma told them.

“Here in Jamaica you may call it Bone Chiller, Star Fade, or maybe Five Day Bush,” I added. “Those are some of the local names we’ve found. No one in the science world has seen or heard of this plant for over thirty years. Has anyone in Guavaberry seen it by chance?”

“Me be remembering a bush named Star Fade,” an older woman spoke. “But me not be be seeing it for a long, long while now.”

The shopkeeper took the illustration and studied it for a long minute, then slowly he shook his head. Others in the shop looked at the distinctive drawing, muttering to themselves. Then one by one they said, “No, not me. Not here. It not be here in our bush.”

“Best you go be asking the Obea mon yourself, down the way,” the shopkeeper suggested. “Me be knowing everything ‘bout salt fish, beer and cigarettes.” Everyone let out a good belly laugh at that. “But nobody,” the proprietor said, “be knowing the bush like that Samuel, that be sure. If that bush be here, that old Obea mon, he be knowing ‘bout it like no other. The Obea man, he be giving us bush medicine. He be the one we go to when we be needing fixing-up.”

Soon we were following a barefoot boy, called by someone to the shop to guide us. We walked down a winding, narrow trail lined with more of those effusive poinsettias, which led us away from the main road. As we approached a wooden hut, the acrid smell of charcoal cooking fires from hidden houses all around, pelted the air with a distinctive, smoky flavor. Thick vegetation hid most of the other huts.

“This be it,” the raggedy little fellow pointed as he loudly sang out, “Inside! Inside, Samuel!” Then the boy scampered back in the direction of the shop, leaving Zuma and me to approach the house on our own.

The Obea man’s hut had once been painted with a cacophony of gay hues, from the peeling scales left on walls now covered by flowers, vines, bones and shells, and all sorts of organic objects that proclaimed the inhabitant’s competent use of the natural world’s many generosities.

A sonorous voice burst from within. “Who that be outside?”

“Hello, Mr. Samuel! We’re here looking for a certain plant that maybe you can help us find,” I sang out in my best, hopeful, cheery tone.

“Someone at the shop told us you might be able to help us,” Zuma chimed, her eyebrows arched in a high V.

“Come inside, then. Me can’t be getting up, me be fearing.” The low-pitched voice returning our call was friendly.

Doors opened wide, shutters thrown back from unbarred windows, we entered a traditional West Indian country dwelling. Stepping through a colorful beaded curtain hanging in the doorway, we immediately were embraced by the warmth of nose-twitching odors, pleasantly familiar to us, because Zuma and I easily recognized titillating aromas of fungi and seeds, bark, leaves and roots of plants we would soon explore. The pungent smell of wondrous sources of herbal knowledge not yet revealed to us, welcomed us, before the man did.

“What bush you be looking for then?” A booming bass voice signaled where the outline of a seated figure could be discerned in the room’s deeply crosshatched shadows.

In a few seconds we adjusted to the room’s dark gloom. And when we did we saw, resting in a fanciful chair made from odd shapes of gnarly wood that had a glow of its own, a gray-haired man whose amiable, smooth face was filled with as much character as his house had sharp and beguiling scents. Enthusiasm shined his eyes, which looked like black diamonds from where we stood.

“Good afternoon. Sorry, me not be getting up today. Twisted me ankle so me be sitting for now. Will you be sitting too? Me name be Samuel Waters.” The man extended a mammoth hand for us to shake. His face exuded friendship, so we relaxed.

In hand-hewn chairs made in a unique fashion out of mysterious wood radiating lustrous halos, we joined the wise-looking old black man and introduced ourselves. There was hardly any space in the room except for a large table and magnificent chairs, four of them, which we settled into. I looked around and saw other neatly carved objects, small sculptures of animals, insects and fish, placed here and there on high shelves. Through a doorway into the only other room in this tiny house was a mosquito net-canopied, handsomely carved bed of the same design as the other hand-hewn furniture in Samuel’s abode. I mentally noted to ask this man about what kind of wood his furniture was made from, and if it were he who made all the exquisitely crafted pieces.

I cleared my throat. “There’s a plant that used to grow only here in Jamaica we’re very interested in finding. Some people think it might be extinct already, but we hope we can prove them wrong. With your help maybe we can find it.”

Samuel’s eyes sparkled even more as he answered.

“Me be helping if me can. What you be wanting that bush for?”

We told him about the cancer research. The Obea man’s expression spread in approval, his face becoming even more appealing. “Oh that be a very good reason, for sure. Keep disease in balance with the bush. Yes, that be best. Let me be seeing that picture you be having, then.”

I was surprised. “How’d you know about our drawing?”

Samuel chuckled. “There be no-thing around here me don’t know about. Someone from the shop be running down here ahead of you and that slowpoke boy. There be eyes and ears in the hills of we that be shaming them fancy telephones.”

Samuel continued chuckling as he brought out a big magnifying glass to closely inspect the fine line drawing I offered him.

After a few seconds the Obea man looked up, nodded his head and grunted.

“That be Star Fade, you can be sure. Must be nearly twenty years ago, me think it was when last me be seeing it.”

Zuma and I grimaced our daunted possibilities at each other.

“You scientists folk might be right, you know,” Samuel continued, “them who say it might be gone. Them business peoples be killing off most of our bush with their recklessness. Nobody seems to care no-thing about the land no more. She be needing us, Lord God Almighty me be knowing that for sure! Everything be changing. Peoples, they only be loving the money. They be forgetting about the bush, good and bad, how it be here helping we, yes sir. Maybe it be gone, like you be saying, Mister Scientist. Them big shots, they be ripping up the bush that be making them no money. Carving out the bauxite for aluminum foil every-body be wrapping they foolish frozen food up in. Shame, shame.” Old Samuel shook his head sadly.

I became impatient with the old man’s tirade and quietly pulled out a map of the local terrain from my knapsack. “Mr. Waters, do you recall about where you might have last seen Star Fade?”

“Me being Samuel be plenty fine, thank you. Let me be seeing that, young science man,” Samuel gently reached for and spread the map over his thin lap.

Looking intently at the topographic layout—which he appeared to instantly comprehend as well as any expert map-reader—the old man traced with a thick, rough finger the imaginary path of remembered wanderings.

“Here,” he quickly pointed. “It be here. Me remember sharp because that be where me run into Mistress Brindup’s cow with she broke leg. Nobody knew what happened to she that day. Just disappeared. Me be finding she, broke down in a small ravine between two hills somewhere, here. The land there, it be too rocky for they little feet of cows, me be telling she, but do Mistress Brindup listen? No. That day me be out gathering the bush for women’s birthing time. There be a rash of twins that year and those double-childs cleaned me out of Rub Up, the bush me be using for hard birthings.

“So me be going up there to pick me some. Me be remembering very clear that Star Fade be growing there. Me be happy seeing it up there, yes sir, because it be very very scarce, even back then. Me never be seeing it again, that be true. Me be forgetting clean about it when me be finding that cow broke down. A few times me be going back looking for the Star Fade because, you know, Obea medicine be needing it something fierce, now more than before. But me never be finding it again. No, not ever. Nobody ever be using Star Fade ‘cept Obea peoples, so no one else be noticing it be gone and disappear. ‘Cept you two now.”

“What’d you use it for, Samuel?” Zuma asked.

Brunfelsia, “Star Fade”

The old man looked up, bounced his head up and down repeatedly with a faraway look in his eye, as if reminiscing all by himself. In a low voice he slowly said, “Star Fade be good for calming down the crazy peoples.” Shaking his head he sighed, as if thinking of a particular incident. “You know how troublesome them be.”

Samuel sighed, then loudly sucked his teeth, West Indian style. He said, “It be making them crazy peoples be taking a deep, peaceful sleep. Long enough for the rum or ganga or whatever it be making ’em go crazy work out of they systems. When they be coming awake, they be fixed. And no-body, no-thing be getting hurt ‘cause them craziness in some be running too strong for any-body be doing anything about it, no sir! Without Star Fade, the crazy peoples, they be troublesome and vexing every-body.”

I understood. Nodding my head I looked deeply into Samuel’s all-seeing, perfectly clear eyes, trying to fathom the depth of his handed-down-for-generations herbal lore.

“And the name,” Zuma asked, “Star Fade, is that because the flowers …”

“… Yes mon,” Samuel answered her without taking his riveted eyes off mine. “They be changing color all the time.”

###

Samuel told us he needed a few days to mend his ankle, so meanwhile, Zuma and I decided to make short forays into the hills surrounding Guavaberry. But our systematic search proved depressingly unsuccessful. Nothing even remotely resembling B. splendida turned up.

At the end of each day we went back to Samuel’s house, at the invitation of his sweet wife, Sarah, to share their simple evening meal. Afterwards we continued our intriguing interchange, this island medicine man and I, a trained scientist, while Zuma helped Sarah and, she told me later, delighted in learning all sorts of Caribbean women’s lore.

We discovered that indeed, Samuel was the gifted woodworker of that spectacular homemade furniture and ornately carved sculpture we saw in every nook and cranny of their home. Each evening after our meal, Samuel would sit outside in his front garden and carve from boughs of strangely luminescent wood. He told us this was his favorite wood, called Kubah-wee. It was extremely hard, impervious to insects, and, he said, “The wood, she be having this inner light all by she own self, like eyes of God.”

###

Samuel’s ankle was well enough on the third day. He wanted to join Zuma and me in our search. We set out early. After a few hours’ walking we came to a place Zuma and I had missed in our own searching. Samuel used a carved walking stick, made from yet another hardwood, more distinctively blood-red than any purple heart I’d ever seen.

Samuel noted: “This be the place where Star Fade might be hiding. Me be showing you. Come.”

We followed Samuel to a narrow trail he accessed by squeezing in between two huge boulders, possibly the reason Zuma and I’d not found it on our own. We found ourselves high along the ridge of one valley, looking down into another, above a maze of dried-out ravines that didn’t resemble any of the other fertile valleys neighboring Guavaberry.

I was surprised at the old man’s agility, so I whispered to Zuma,

“For a man who’s got to be at least seventy Samuel’s remarkably fit, wouldn’t you say?”

“Me be eighty-two!” Samuel loudly proclaimed with verve in his braggadocio laughter. He hadn’t even turned around, but continued leading the way, brandishing a machete like a strong young man in one hand, while with the other, he leaned slightly on his smoothly carved cane. I laughed, too, and asked him as we walked:

“So what’s your secret, Samuel? I don’t see you abstaining from anything. Wasn’t that a Red Stripe beer and a cigarette I saw you have when that fellow came by last night? What gives you such good energy for your age?”

Samuel stopped for a moment and turned to face us, using the walking stick as a prop in the rugged turf. Brambles and stickers were everywhere now, something Zuma and I hadn’t seen anywhere in our previous days’ hikes, looking for splendida. The land had suddenly, drastically changed. After slowly machete-ing our way along this ridge for the last hour, the lushness of Jamaica’s interior had shifted to something else, entirely different.

“Me not be doing too much any one thing,” Samuel said. “Me use the bush the Goodness be giving we for everything. If me be sick, me be having a bush for it. If me feeling sad or vexed there be a bush to be raising me back up. If me feeling out of sorts with me family or the village, me be finding the bush to be making that hurt better, too. Yes, mon,” Samuel turned around and resumed his brisk pace of hacking away with a perfectly honed machete, “there be a bush that our Maker be putting on the land taking care of any trouble of we. Best you believe, then you might see. That be why me be the Obea mon around here. Other folks, they be running off to town, coming back with they do-nothing pink pills from fancy doctors that be knowing nothing ‘bout miracles that be waiting for we, right here in the bush.”

###

We cleared the apex of that rocky climb and came out upon an even higher place, where we could overlook a startlingly barren area below. The three of us stopped and stared. I couldn’t help but whistle lowly and say, “Geez, what happened here?” Zuma was speechless. I looked at her face and felt her sorrow. It was painful, to see this once-fertile land so obviously raped of its soulful nourishment. Even though it’d been some time before, from the accumulation of the thick scrubby undergrowth, it was obvious that something terrible had once ruined this land for any use other than bauxite mining, which had taken place decades before, Samuel informed us.

“There,” Samuel pointed to the horizon. “There be the place, what’s left of it. Where Mistress Brindup’s cow be, years gone by. See that? The land be a mix-up, from the old bauxite days.”

Samuel pointed to a small rise of land about a thousand yards away. The spot he’d been leading us to, he said.

“Mix-up?” I said, looking at an isolated, tiny plateau of land through the binoculars. “That doesn’t even begin to describe how queer this place looks.”

What we saw in front of us—in the middle of a brown field of complete flatness, was a solitary skinny butte that arose, topped by a tassel of green poof, as if the land itself were giving us the finger. It was a peacock’s shocking display, like a huge, garishly beautiful and regally alive bird amidst a field of drab, exceedingly thorny twigs. The tall, skinny altar of land that hovered above this sparse valley floor was about sixty feet high, and no more than fifty in diameter. I figured that long-ago, marauding bulldozers must have overlooked this prominently jutting table of tree-topped earth—or someone had been anxious to call it a day. Hidden in that forgotten valley, far from the lushness we’d seen elsewhere in Jamaica, lay this valley—an undulating mess of wiry brush. You could see the valley’s devastation reaching to where the next hillside swept up, where the next green valley, and the next, grew as fertile, as gorgeous as it did everywhere else on the island. Further east, the land thrust up to gradually become the Blue Mountains, towering seven thousand feet in the distance.

I studied the situation. “You’re right, Samuel, if any place could be a natural sanctuary, that freaky little butte is it.”

It took us another two hours to machete our way through the tangled mass of thick thorny vines and prickly brush to reach the peculiar rise of land, which had an odd, solitary, scrawny guava tree growing at its apex, like a parched flag announcing the land’s supremacy over humanity’s destruction, killer-dozers, and land leeches. The butte’s crown was made of slightly greener, and not-so-straggly brush. Around the paltry shelf of land, the land begged for mercy, so unlike the rest of the dense verdant growth of this jade island.

We finally reached the butte. While Samuel rested, Zuma and I climbed the steep sides of the lone crest. For the first time that day Samuel held back. He sat under a young ficus tree at the base of the butte, its buttress roots spread out in a complicated system of support and interdependency. Many diverse ferns, mold, lichen, orchids, vines, and fungi combined to form a tightly squeezed flora-condo on its bark, within the tree’s intricate nooks and crannies. I noted how the life forms were returning there, in the hospitable environment of the tree’s protection.

As we climbed we heard Samuel loudly grumble to himself. “This rotten land be needing a serious cut-up an’ burn. Cattle needs to be coming back and manure this place back. They gots to be eating more than thorns that be pushing up everywhere. It be dread here, dread. Shame, shame.”

A continuous stream of lips sucking against teeth could be heard as Zuma and I made our way up the slope.

Quickly we pulled ourselves up, using roots as footholds. In this forgotten valley a horror-movie landscape surrounded us like a bad-news 3-D diorama. Standing up on the plateau itself, I felt like we’d arrived at a lookout over a barren planet. Everything in that valley was so unnaturally un-tropical: nothing reminded us of lush. We looked and looked … and all we could see was a manmade valley of desolation.

“It’s inconceivable,” Zuma murmured, “that this little pimple of land could have escaped intact while everything else—was destroyed.”

I didn’t answer. I was too busy inspecting every bush, every scrawny plant the cliff-sided mini-mesa had preserved—like it was an elevated time capsule. It was spooky up there, the bizarre growth resembling leftovers from the valley floor below, now ravaged and raped of its topsoil. Going from plant to plant I sensed this little butte had, for decades perhaps, been untouched. I could see this from the conspicuous, albeit stunted, mature growth pattern. Crawling under some dwarfed monsteras that shielded many smaller plants from the harsh, unmerciful sun up there, I found some familiar-looking plants.

“Look! I can’t believe it, Zuma! I think it’s here. Yes! It really is!”

She rushed over to where I crouched on the plateau. A perpetually dangling loupe around my neck, the clippers in their leather holster, attached to my belt, must have made me appear the quintessential Plant-Man. I gently pushed back the thick, tangled overgrowth—till finally I held a very puny, extremely gnarly, woody bush in my quivering fingers. Crouching over it, I examined its leafy nodes, its knotty bark. In my ears I could feel my excited heartbeats.

“Could we be so lucky, Carlos?” Zuma whispered behind me, wondering how that runt plant I was inspecting could be anything special.

With an elation usually reserved for my rare but profound perceptions into the secrets of the natural world’s mysteries—or hearing a rapturous Chopin sonata, perchance—I faced her, my fellow plant rescuer.

“This is it! Zuma, what a piece of luck! Look how stunted it is, but it’s alive! It’s supposed to be a man’s height, yet look—you can tell it’s been growing here for at least twenty, maybe thirty years from its thick bark. It’s incredible! Look how mutated it is, look! We would never have found this specimen, never! if it hadn’t been for Samuel. Look, here’s another mature one over here. And look, seedlings, over here, beneath this other one. This is a damn miracle!”

We shouted down to Samuel that we’d found Star Fade.

“Me be happy hearing that, me son,” he called back. We heard him make whooping noises. He struck up a popular calypso tune. Bass notes rang out: “Sugar boom, sugar boom boom,” greeting our own wild jubilation in uplifting, satisfying noise.

Old Samuel continued to sing and rejoice as we gathered specimens. We found mature, viable seeds, enough to safeguard this species’ continued evolution, at least for our lifetime.

Samuel wasn’t surprised, he told us when we came back down, how people can’t stop nature when she has a mind to survive.

“The ways of the land, they be deep and they be mysterious,” the old man softly said. “Me always be finding the way she, our Mother Nature, be much more than me, or any-body, ever be knowing. She be outwitting us all, just you be watching and seeing. The land, she be guarding she powers for such as you two be coming to find again, be taking them back from they secret place she put them safe in. No big pocket mons can kill out she mother ways of the good good earth, no sir. The land, she be kind to us.”

Old Samuel took a handkerchief from his worn pants to wipe his forehead. For a brief moment, it looked as if he might weep.

“Me be glad,” he said clasping us both on the shoulders when we showed him the splendida seedlings Zuma and I had placed in protected containers, along with its risen-from-the-dead seeds we’d found; everything safely nestled in moist cotton in plastic baggies. In my backpack were a few precious sprigs of cut specimens already pressed, ready to take back and study.

“Yes sir, me be glad you young science folks be coming to help we be getting our Star Fade back,” the old man said.

Acting like he was our own proud father, we showed Samuel the seedlings and seeds we were entrusting to him, knowing he’d raise them well until he could transplant them back into their wild origins, in a protected area, of course.

“Now maybe the world not be having such troubles with them crazy peoples like it be doing,” Old Samuel said with satisfaction. Relief flooded his strong body, a potent remedy of its own. A bright smile crossed Samuel’s dark face as we turned to head back to share one last delicious stew pot of Sarah’s concoction before Zuma and I would fly back to the States to grow and share our seeds, to write and to draw, and declare splendida, a species once thought extinct, had now been miraculously found.

“They be some wicked Jumbies, them spirits that walk along with us, that be running a-feared for they evil ways tonight, me son!” Samuel shouted loudly as he triumphantly thrust his cane into the air.

Overhead the fading afternoon sun beamed as we walked back.

Zuma be happy now, yes mohn!