Developing the Willingness to Change

Why do you think the topic of willingness to change comes after Finding the Courage (see the previous Maya post, September 15) instead of before it? I’m asking that to help gather my thoughts. Originally, these chapters-headings came to me in a flash, in quick succession, when I first decided I wanted to write about this subject of change. Without courage, of course, nothing is possible. A person can’t even leave their house without a certain amount of courage to open the door and leave their familiarity, evidenced by the disorder of agoraphobia that many people suffer from.

So yes, courage has to come first!

But this willingness thing is something that is closely tied to courage, yet very different in that it encompasses much more action, much more persistence and daily reinforcements, sometimes hourly recommitments, than what it takes to muster up the initial courage to change that begins our journey of spiritual transformation.

Willingness, at least to me, means that I’m ready to try on different things, maybe many things, until I find those that work better than what I had before, or—at the least, I get to reinforce that my “old familiar ways” work best for me after having given due credit to other methods. Applying this theory of willingness to something simple, let’s talk about, say … how to paint a room.

Some painters think they have the best method; others claim no, theirs is the most effective. In my experience there is always room for improvement in the area of “how to” do just about anything, from peeling a garlic clove to tuning a carburetor (no, I don’t know how to do that!) to applying paint to a surface. But before us now we’re talking about something a little more serious: how to change one’s attitude toward life, the subject of this writing.

For life changes, Willingness means to be open to another philosophy, another perspective, point of view, another creed, another faith even, than what we have been used to measuring our experiences as right, worthy, or true.

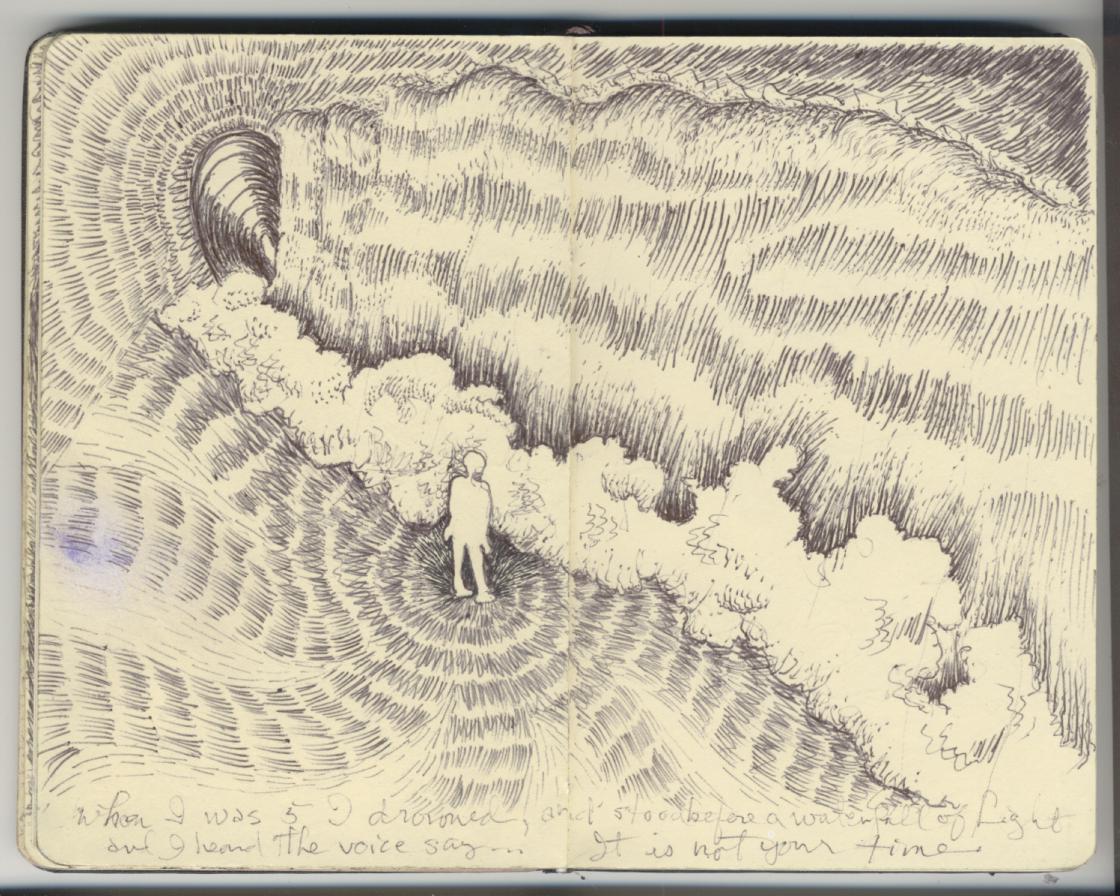

Some of us never think about what we believe in. We just live our lives, and do what our parents taught us to do. Others set out to rebel and do everything the opposite of how we were raised. In my case, I was extremely uncomfortable with a lot of rigid social customs, dictates and dogma that I was handed in my parent’s home, and by the particular religion in which I was raised. Another person might never have had any religion, political view, or any formal structure of life-thought introduced to them in their home of origin. But for me, when I reached the age when we all begin thinking about what life is, what its meaning might be or if it even has one, and things like what might happen after death and before birth — the subject of truth, my truth, intrigued me from my earliest recollections.

The core of what we’re discussing here in Maya’s Book of Change is what life is all about. Not my life, but your life. Only you can discover what your life means to you. Because my friend Maya is facing the end of her life, battling brain cancer the best she can under the most severe circumstances of impending doom, having received the death sentence her oncologists spelled out to her in black-and-white — all the radiation, chemotherapy, surgeries and other modalities of healing she does, they say to her, only postpone the inevitable demise she’s facing. Unless, of course, a miracle occurs, which I always believe can happen, and of course, so does Maya.

I say these things to remind us about our journey together, how we’re exploring spiritual change here. Sharing Maya’s story is not about pitying her. No, on the contrary. We can celebrate because already, Maya has shown quite a change in her thinking. Today, she is forgiving of what used to be unforgiveable to her. She is detached, where before getting cancer she was committed to her anger and incapable of forgiveness. I credit her change of heart, this radical change of thinking to her having the terminal disease of glioblastoma, the most voracious of brain cancers that fate hands a person.

Currently, four months into her diagnosis, with the large tumor removed, yet knowing the cancer still spreads in her brain like veins in blue cheese, Maya is in a sweet stage of acceptance. Having gone through many weeks of grief, tears, lamentations, and plenty of “why me’s!” she’s now willing to look at the stark reality of her life. Now she can admit, and prepare, for the fate that draws ever close to her. And each one of us, truly, is in a varying degree of the same situation that has befallen Maya: the imminence of our death.

Yet I cheerily say to my friend, “Maybe I’ll die before you do, Maya, you never know! Maybe I’ll get run over by a truck this afternoon, or get done in by a shark attack during my daily ocean swim.” I say these things not to invite negativity into my life, but—to empathize with my friend. Maybe I will succumb to something just as deadly before Maya actually dies of incurable cancer, is what I’m saying to her. Having cancer is no guarantee that her life is definitely going to be shorter than mine, if something as unpredictable and shocking as sudden death, a reality of life, happens to be my destiny.

Just because a person has a terminal disease—call it bum luck or a rotten deal of the life-cards we’re each given by providence—doesn’t mean a person can’t have a good life, a terrific day, week, month, with whatever time they’ve got.

(this is the 6th installment in the “Maya’s Book of Change” series. See August 7, 2011 post on Lordflea for beginning of series.)